Devolution represents a significant framework for governance, embodying the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to subnational entities, such as regional or local authorities. This process is essentially a form of administrative decentralization, empowering these devolved territories to legislate on matters pertinent to their area, thereby granting them a notable degree of autonomy in their governance. It allows for decision-making to be brought closer to the communities it affects, fostering a more responsive and regionally tailored approach to public policy and service delivery.

Understanding Devolution: A Framework for Governance

At its core, devolution is about sharing power within a unitary state. Unlike a purely centralized system where all major decisions emanate from the capital, devolution enables distinct parts of a country to manage their own affairs within a specified legal framework. This can encompass a wide range of responsibilities, from education and health to aspects of local taxation and environmental policy, reflecting the unique needs and aspirations of different regions.

Devolution Versus Federalism: Key Differences

While both devolution and federalism involve the distribution of governmental powers, they are fundamentally distinct in their legal underpinnings and the degree of permanence of that power distribution. Understanding these differences is crucial:

- Nature of Power Delegation: In a system of devolution, the powers granted to subnational authorities are statutorily delegated. This means they are conferred by an act of the central parliament. Conversely, in a federal system, the powers of sub-unit governments (like states or provinces) are constitutionally enshrined.

- Reversibility: A defining characteristic of devolution is that the delegated powers, while substantial, are generally temporary and reversible. The central government retains ultimate sovereignty and can, through ordinary legislative processes, repeal or amend the legislation that created the devolved bodies. This means the state remains, in legal terms (de jure), unitary.

- Constitutional Guarantee: In stark contrast, federal systems guarantee the existence and powers of their sub-units within the national constitution. The central government cannot unilaterally withdraw these powers; doing so would typically require a complex process of constitutional amendment, often necessitating the consent of the sub-units themselves.

- Protection of Sub-units: Consequently, sub-units under a devolved arrangement possess a lower degree of legal protection for their autonomy compared to their counterparts in a federal system. Their powers are vulnerable to change by the central legislature, whereas federal sub-units are shielded by the constitution.

The Scottish Parliament: A Case Study in Devolution

The Scottish Parliament, known in Scottish Gaelic as Pàrlamaid na h-Alba and in Scots as the Scots Pairlament, stands as a prominent example of a devolved legislature. It serves as Scotland's unicameral (single-chamber) law-making body, playing a crucial role in the nation's governance.

Historical Roots and Revival

Scotland once possessed an independent national legislature, the original Parliament of Scotland, which operated from the early 13th century. This historic institution ceased to exist in 1707 when the Kingdom of Scotland united with the Kingdom of England under the Acts of Union, forming the Kingdom of Great Britain. This pivotal moment led to the dissolution of both the Scottish and English Parliaments, giving rise to the Parliament of Great Britain, which convened at Westminster in London.

Centuries later, a powerful public desire for greater self-governance emerged. This culminated in a landmark referendum held in 1997, where the Scottish electorate decisively voted in favour of establishing a devolved legislature. Responding to this democratic mandate, the United Kingdom Parliament passed the Scotland Act 1998, which meticulously defined the powers and legislative competence of the new Scottish Parliament. On 12 May 1999, the modern Scottish Parliament met for the very first time, marking a significant new chapter in Scotland's constitutional history.

Structure and Electoral System

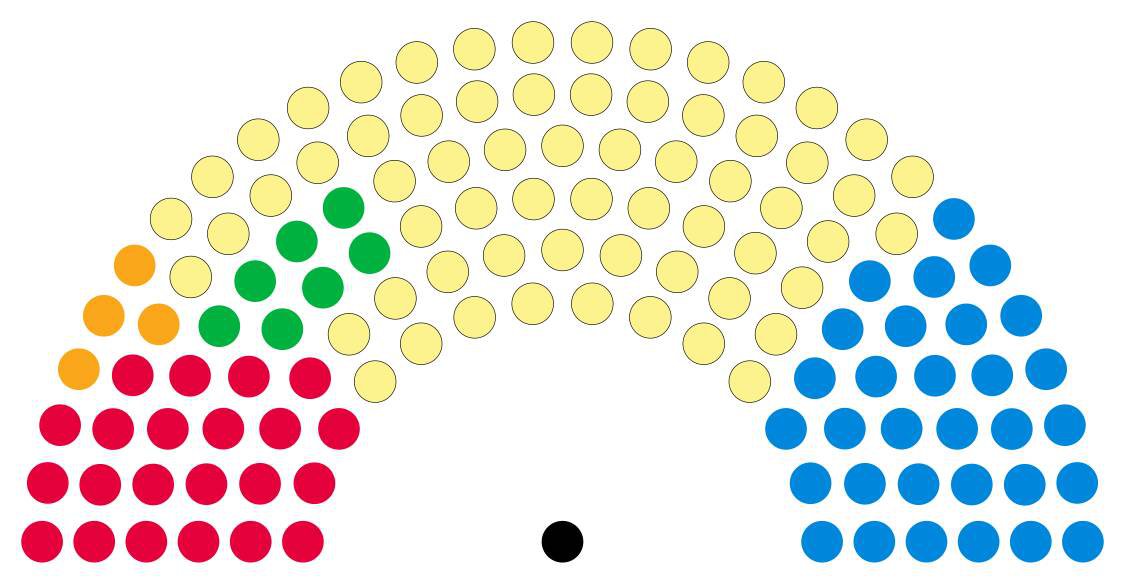

The Scottish Parliament is situated in the distinctive Holyrood area of Scotland's capital city, Edinburgh, and is often referred to simply as "Holyrood" through the use of this geographical metonym. It is a democratically elected body comprising 129 members, each known as a Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP). These MSPs serve five-year terms, elected through a sophisticated electoral mechanism known as the additional member system, designed to combine strong local representation with a more proportional national outcome:

- Constituency MSPs: Seventy-three MSPs are elected to represent individual geographical constituencies. These are chosen by the plurality (or "first-past-the-post") system, where the candidate with the most votes in a given area wins.

- Regional List MSPs: A further 56 MSPs are returned as list members from eight additional member regions across Scotland. Each of these regions elects seven party-list MSPs, ensuring a degree of proportionality that might not be achieved solely through the constituency-based system. In total, each region elects between 15 and 17 MSPs, encompassing both the seven regional list members and the constituency MSPs whose areas fall within that region.

The most recent general election to the Parliament took place on 6 May 2021, which saw the Scottish National Party secure a plurality of seats.

Legislative Powers and Evolving Competencies

The Scotland Act 1998 laid down a clear division of powers. Rather than listing everything the Scottish Parliament could do, the Act specifies a set of powers that are "reserved" exclusively to the Parliament of the United Kingdom at Westminster. This means the Scottish Parliament possesses the authority to legislate on all matters that are not explicitly reserved. Reserved matters typically include areas like defence, foreign policy, and broad macroeconomic policy. However, the UK Parliament maintains the inherent ability to amend the terms of reference for the Scottish Parliament, allowing it to either expand or reduce the areas in which Holyrood can make laws.

Since its inception, the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament has undergone several significant amendments, reflecting an ongoing process of constitutional development within the UK. Notably:

- Expansion of Powers: The Scotland Act 2012 and the Scotland Act 2016 considerably broadened the Parliament's powers, particularly enhancing its responsibilities over taxation and welfare. These acts granted Scotland greater fiscal autonomy and the ability to tailor certain social policies more closely to its own context.

- Challenges from the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020: Following the UK's departure from the European Union (Brexit), the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 was introduced. This Act aims to prevent regulatory divergence among the UK's devolved nations by imposing principles of market non-discrimination and mutual recognition across the UK internal market. While it does not, on paper, alter the specific devolved competencies, its practical effect is to constrain the manner in which these competencies can be exercised. Critics argue that this legislation potentially undermines the Scottish Parliament's freedom of action, its regulatory competence, and its overall authority, limiting its ability to make different economic or social choices compared to those made by Westminster. It represents a significant development in the delicate balance of power within the UK's devolved settlement.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Devolution and the Scottish Parliament

- What is the fundamental difference between devolution and federalism?

- The core difference lies in the permanence and origin of power. In devolution, powers are delegated by the central parliament and can be reversed or amended by it. The state remains legally unitary. In federalism, powers are constitutionally guaranteed to sub-units and cannot be unilaterally withdrawn by the central government, requiring constitutional amendments.

- Why was the Scottish Parliament re-established?

- The modern Scottish Parliament was re-established following a referendum in 1997, where the Scottish electorate voted in favour of creating a devolved legislature. This reflected a strong democratic demand for greater self-governance and decision-making closer to the people of Scotland, following centuries of being governed solely by the UK Parliament after the 1707 Acts of Union.

- What powers does the Scottish Parliament have?

- The Scottish Parliament has the power to legislate on all matters that are not explicitly "reserved" to the UK Parliament by the Scotland Act 1998 and subsequent amendments. These non-reserved areas include key public services like education, health, justice, environmental policy, and aspects of taxation and welfare. Reserved matters typically include defence, foreign affairs, and broad macroeconomic policy.

- How are Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) elected?

- MSPs are elected through an additional member system. This combines two methods: 73 MSPs are elected directly from geographical constituencies using the "first-past-the-post" system, and a further 56 MSPs are elected from eight regional party lists to achieve a more proportional outcome overall. Each region ultimately elects a total of 15 to 17 MSPs (seven from the regional list plus the constituency MSPs within that region).

- Has the power of the Scottish Parliament changed over time?

- Yes, the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament has evolved. The Scotland Acts of 2012 and 2016 significantly expanded its powers, particularly in areas like taxation and welfare. However, the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 introduced new requirements aimed at preventing regulatory divergence post-Brexit, which, while not changing powers on paper, practically restricts the exercise of some devolved competences and has been seen by some as undermining Holyrood's autonomy.

- What is the significance of the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 for Scotland?

- The UK Internal Market Act 2020 is significant because it seeks to maintain a coherent internal market across the UK after Brexit. It does this by imposing principles of market non-discrimination and mutual recognition. While its stated aim is to prevent regulatory barriers, critics argue that it practically limits the Scottish Parliament's freedom to make different economic or social policy choices from Westminster, even in areas that are nominally devolved, potentially undermining its ability to adapt policies specifically for Scotland's unique needs.

English

English  español

español  français

français  português

português  русский

русский  العربية

العربية  简体中文

简体中文