The American Revolutionary War: Securing American Independence

The American Revolutionary War, also widely recognized as the Revolutionary War or the American War of Independence, was a pivotal conflict that ultimately secured the independence of the United States of America from Great Britain. This transformative struggle commenced on April 19, 1775, with the "shot heard 'round the world" at Lexington and Concord, culminating eight years later with the official acceptance of American sovereignty by Britain on September 3, 1783.

Roots of Rebellion: Colonial Autonomy and Growing Tensions

For over a century, American colonies, established through Royal charters in the 17th and 18th centuries, had developed a significant degree of self-governance. They were largely autonomous in their domestic affairs, possessing their own legislative assemblies and legal systems, which fostered a strong sense of local identity and self-reliance. Economically prosperous, these colonies engaged in robust trade not only with Britain and its Caribbean territories but also, through Caribbean entrepôts, with other European powers. This period of salutary neglect allowed a distinct American identity to flourish.

However, the British victory in the global Seven Years' War (known as the French and Indian War in North America) in 1763 dramatically altered imperial policy. Burdened by immense war debt and seeking to assert greater control over its vast empire, Britain began implementing a series of policies that provoked widespread colonial resentment. Tensions escalated significantly over issues of trade regulation, colonial expansion into the Northwest Territory, and, most notably, taxation measures designed to raise revenue directly from the colonies. Key examples include the Stamp Act of 1765, a direct tax on printed materials, and the Townshend Acts of 1767, which imposed duties on imported goods like glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea.

What were the immediate consequences of these British acts?

Colonial opposition to these acts, often framed as "taxation without representation," grew increasingly vocal and organized. This dissent tragically escalated into violence with events like the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, where British soldiers fired into a crowd of protesting colonists, killing five. Further defiance was epitomized by the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, where Sons of Liberty activists destroyed an entire shipment of tea in protest of the Tea Act. In response, the British Parliament enacted a series of punitive measures in 1774, collectively known by the colonists as the "Intolerable Acts" (officially the Coercive Acts), which further curtailed colonial self-governance in Massachusetts and closed the port of Boston.

From Petition to Armed Conflict: The Path to War

In a unified show of resistance, the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774. Delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies drafted a Petition to the King, articulating their grievances and demanding the repeal of the Intolerable Acts. They also organized a widespread boycott of British goods, aiming to exert economic pressure on Parliament. Despite these earnest attempts to achieve a peaceful resolution and restore harmonious relations with the Crown, reconciliation proved elusive.

Fighting irrevocably commenced with the Battle of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, marking the onset of open hostilities. By June 1775, the Second Continental Congress, recognizing the need for a unified military force, authorized the creation of the Continental Army and appointed George Washington as its commander-in-chief. Although a faction within the British Parliament, including prominent figures like Edmund Burke and William Pitt the Elder, vocally opposed the "coercion policy" advocated by Prime Minister Lord North's ministry, both sides increasingly came to view armed conflict as an inevitable path. The Olive Branch Petition, a final plea for peace sent by Congress to King George III in July 1775, was summarily rejected. In August, Parliament formally declared the American colonies to be in a state of rebellion, setting the stage for full-scale war.

Key Campaigns and Crucial Foreign Alliances

Following the strategic loss of Boston to the Patriots in March 1776, Sir William Howe, the newly appointed British commander-in-chief, launched the extensive New York and New Jersey campaign. He successfully captured New York City in November 1776, a significant blow to the American cause. However, General George Washington's daring and strategically brilliant victories at Trenton in December 1776 and Princeton in January 1777, though small in scale, provided a vital boost to Patriot morale and demonstrated the Continental Army's resilience. These successes were crucial in preventing the collapse of the American war effort during a critical period.

In the summer of 1777, Howe succeeded in taking Philadelphia, the American capital, forcing the Continental Congress to flee. Yet, a more decisive blow for the American cause occurred in October 1777: a separate British force under General John Burgoyne, attempting to sever New England from the other colonies, was compelled to surrender at Saratoga, New York. This victory was monumental, as it conclusively demonstrated that the American Patriots were capable of defeating a large British army in a conventional engagement. The Battle of Saratoga was a crucial turning point, significantly convincing major European powers, particularly France and Spain, that an independent United States was a viable and worthy entity, capable of securing its own sovereignty.

The Franco-American Alliance: A Decisive Partnership

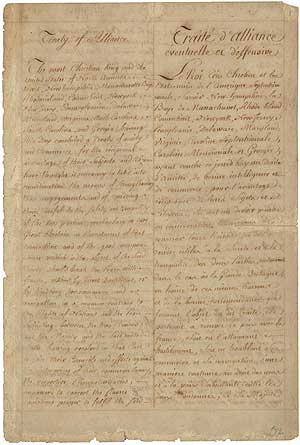

From the outset of the rebellion, France had provided the United States with informal economic and military support, including covert shipments of arms and supplies. However, the American triumph at Saratoga solidified France's commitment. On February 6, 1778, representatives of King Louis XVI of France and the Second Continental Congress signed two landmark agreements in Paris: the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and the Treaty of Alliance. These instruments, sometimes collectively referred to as the Franco-American Alliance or the Treaties of Alliance, also included a secret clause providing for the entry of other European allies, such as Spain.

What were the core components and significance of these treaties?

- The Treaty of Amity and Commerce:

- This treaty marked a monumental diplomatic achievement: France became the first nation to formally recognize the United States as a sovereign and independent nation. It also established mutual commercial and navigation rights between the two nations, openly defying the restrictive British Acts of Trade and Navigation (Mercantilism), which had long limited American access to foreign markets and dictated their trade patterns. This was a direct challenge to British imperial economic policy.

- The Treaty of Alliance (French: traité d'alliance (1778)):

- This agreement formalized a defensive alliance between the Kingdom of France and the United States. Recognizing that the commercial and diplomatic ties established by the Treaty of Amity and Commerce would likely provoke hostilities between France and Britain, this treaty guaranteed French military support in such an event. In return for France's guarantee of American independence, the Congress agreed to join France in its broader global war with Britain and pledged to defend the French West Indies. A critical provision of this treaty was that neither nation could make a separate peace with Britain, ensuring a unified front until American independence was secured. It was initially conceived as a permanent defensive pact, binding the two nations together.

The successful negotiation of these treaties is widely regarded as the "single most important diplomatic success of the colonists." It represented the United States' official entry onto the world stage as a recognized nation and formalized the crucial French recognition and support that proved decisive in America's victory. Immediately following their signing, France provided substantial material, military, and financial aid to the American cause, including vital loans, arms, uniforms, and the deployment of the French Navy and troops under commanders like Rochambeau and Lafayette. Some historians consider the signing of the Treaty of Alliance as marking America's de jure (legal and formal) recognition as an independent nation, solidifying its status on the international stage.

Spain, while not formally allying with the Americans, nevertheless joined France against Britain in the Treaty of Aranjuez (1779). This alliance indirectly benefited the American cause immensely. Access to ports in Spanish Louisiana allowed the Patriots to import much-needed arms and supplies, bypassing British blockades. Furthermore, the Spanish Gulf Coast campaign, led by Bernardo de Gálvez, successfully deprived the Royal Navy of key strategic bases in the south, diverting British resources and attention.

The War's Climax and Peace

The entry of France and Spain into the war profoundly undermined the British strategy devised by Sir Henry Clinton, who replaced Howe as commander-in-chief in 1778. Clinton's strategy shifted the main focus of the war to the Southern United States, aiming to exploit perceived Loyalist sentiment. Despite some initial British successes in the Southern theater, the tide turned decisively. By September 1781, British General Lord Cornwallis found his forces besieged by a combined Franco-American army and naval blockade at Yorktown, Virginia. After a desperate attempt to resupply the garrison failed, Cornwallis was compelled to surrender in October 1781, effectively ending major fighting in North America.

Although Britain's wars with France and Spain continued for another two years in other parts of the globe, the surrender at Yorktown dealt a fatal blow to British resolve to continue fighting in America. In April 1782, the North ministry was replaced by a new British government that, acknowledging the insurmountable cost and futility of continuing the war against the Americans, finally accepted American independence. Negotiations for peace commenced, culminating in the Treaty of Paris, which was formally ratified on September 3, 1783. This treaty officially recognized the United States as a sovereign and independent nation, defined its borders, and granted it fishing rights off the coast of Newfoundland.

How were the broader global conflicts resolved?

While the Treaty of Paris resolved the conflict with the United States, separate Treaties of Versailles were signed on the same day to resolve Britain's conflicts with France and Spain, bringing an end to the wider global hostilities ignited by the American Revolution.

The Treaty of Alliance: Legacy and Later Annulment

Despite its immense significance in securing American independence, subsequent complications arose with the Treaty of Alliance. The French Revolution and the ensuing Napoleonic Wars created a complex international environment. The United States, under President George Washington, found itself caught between its alliance obligations to revolutionary France and its desire to maintain neutrality and avoid involvement in European conflicts, particularly after Jay's Treaty with Britain in 1794. Tensions escalated further with the XYZ Affair and the Quasi-War with France in the late 1790s. These factors ultimately led to the annulment of the Treaty of Alliance by the turn of the 19th century. This period marked a significant shift in American foreign policy, with the United States largely eschewing formal military alliances until the advent of the Second World War, pursuing a policy of isolationism that would characterize much of its early history.

English

English  español

español  français

français  português

português  русский

русский  العربية

العربية  简体中文

简体中文